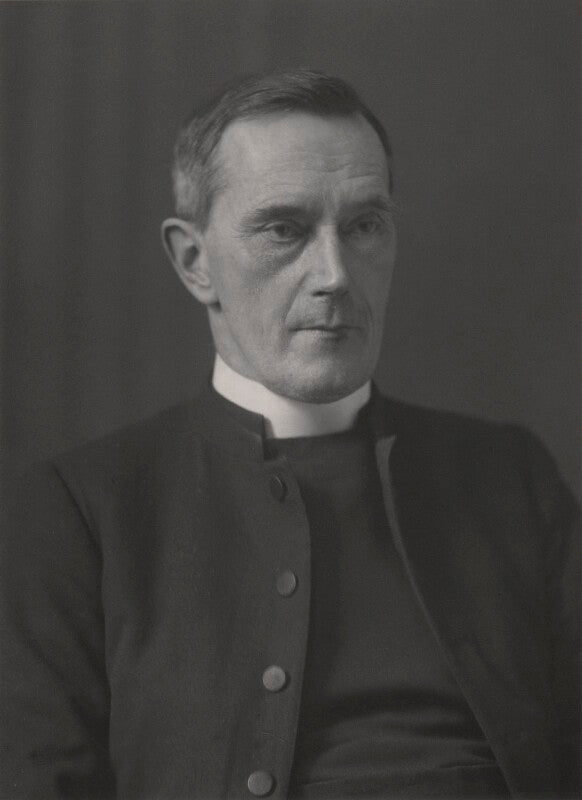

W.R. Inge, The Church and the Age (1911)

-“there are many spirits of the age, most of them evil” … “the Church must not be identified with any particular institution or denomination, or any tendencies which seemed to be dominant in our generation. The Church was a Divine idea which required tens of thousands of years to reach its full development. They must not secularise its message and endeavour to reach men’s souls through their stomachs.”

W.R. Inge, Diary of a Dean (1949)

-“if you marry the Spirit of your own generation you will be a widow in the next.”

“The late Dean Inge summed up the matter, with his characteristic wit. In answer to the argument that the Church must be up-to-date and go along with the times he answered, ‘If the Church marries the spirit of this age, she will be a widow in the next.’ ”

R.S. Thomas

-“who marries the spirit of his age will be a widower tomorrow”

John R.W. Stott

-“men-pleasers, whose main objective is to be trendy rather than godly… We need to heed this criticism. The lust for popularity is indeed imperious, and many of us are twentieth century Pharisees who love ‘the praise of men more than the praise of God’. (John 10:43) One of the most trenchant critics of this tendency was W. R. Inge, Dean of St. Paul’s Cathedral from 1911 to 1934. Invited to lecture in 1911 on ‘The co-operation of the Church with the spirit of the age‘, he declared … ‘there are many spirits of the age, most of them evil’ and ‘if you marry the spirit of your own generation, you will be a widow in the next.’ This is a wise warning.”

Preface

Though it is not usual for a showman to begin by disparaging his own wares, I feel that some apology is needed for printing addresses which were not written for publication, which were delivered to a very quiet little society of London ladies, and the theme of which was neither chosen by the lecturer nor particularly congenial to him. I am also reluctant even to seem to have been provoked to justify myself against the absurd misrepresentations of the halfpenny newspapers and their reporters. I am printing these addresses not on their account, but in deference to strong requests which I could hardly disregard, from those who heard them and many others. The latter, I fear, will find my remarks less bold and original than they had been led to expect.

I approached my allotted theme with a slight feeling of irritation, as I pictured to myself the kind of treatment of it which was probably expected from me. I have lived long enough to hear the Zeitgeist invoked to bless very different theories. When I first began to read books on great subjects, the Spirit of the Age was supposed to be a rationalist in religion, an absolute idealist in philosophy, a materialist and determinist in natural science. Now all these opinions are out of fashion, with the individualism that was often associated with them ; and a new set of catchwords has taken their place. Forgotten truths and discarded errors have emerged again, hand in hand, from their hiding-places. So the rhythm of human thought is maintained ; the slow pulsation of the racial life goes on.

Now it is not the office of the Church ot Christ to be a weathercock, but to witness to the stable, eternal background in front of which these figures cross the stage, and so to preserve and maintain precisely those elements of the truth which are in most danger of being lost. For this reason, it rarely happens that the Church can “co-operate” with a popular movement ; more often it is compelled to protest against its onesidedness. If we consider at what periods the Church has been most true to itself, and has conferred the greatest benefits on humanity, we shall find that they have been times when Churchmen have not been afraid to be “in the right with two or three.” Like certain ministers of state, the Church has always done well in opposition, and badly in office.

The only possible explanation of this is that Christianity is essentially a struggle for an independent spiritual life. It can mould society from above, as it were, but it can never entangle itself with any human institutions without disastrous results to itself and them. The new birth is admission into the citizenship of a spiritual kingdom ; and the citizens of a spiritual kingdom must maintain complete independence in face of all external conditions. The Christian, it has been said, is the Lord’s servant, the world’s master, and his own man. If this is true, there is much in the prevailing tone and temper of modern thought which is a standing menace to the Christian spirit. “The substance of the spiritual life,” says Eucken in one of his latest books,1 “is threatened by the fact that the omnipotent State is inclined to treat that life, in all its branches, as a mere means towards the attainment of its own particular aims ; to look upon science and art, and especially religion and education, with a view to what they achieve for the aims of the State, and to shape them as much as possible in accordance with these aims ; there is also a strong tendency to follow the same course to accomplish the ends of the contemporary form of government. An independent and genuine spiritual life can hardly offer too great an opposition to such a perversion, with its deification of human forms. . . . Nothing can save us from sinking to be mere puppets of the soulless mechanism of the State, if we do not find the power to maintain the life of the soul against all attempts of encroachment.” This is no imaginary danger. Not long ago I read in a periodical edited by a highly placed ecclesiastic, and an ardent social reformer, the following words over the signature of the editor himself, “To the State, and the State alone, we must look for salvation.” And about the same time a prominent socialist said in my hearing to an audience largely composed of clergymen, “The Church is an organ of the State” ; and no one but myself cried “No, no,” at this impudent Erastianism. A church that was an organ of the State would be useless for any purpose except that of helping the State to crush liberty and silence prophets, a task that has no doubt been congenial to some churchmen.

1 Life’s Basis and Life’s Ideal, p. 359, 360.It is unfortunate that those among us who have a firm grasp of the truth that the Church must be independent of the State are for the most part influenced either by jealousy of the Church of England or by the strangely external and mechanical theory of Catholicity which prevails in High Anglican circles. A church does not necessarily lose its spiritual independence, nor its liberty of opposing the temporal power, because it has a recognised position as an estate of the realm. It is by no means certain that our Church would become more independent after disestablishment, especially if the lax and tolerant control of the Nineteenth Century State were exchanged for subservience to “Catholic tradition,” the dead hand of mediaeval theory and practice. The living Spirit of Christ is plainly no respecter of persons or of denominations ; and it is this living Spirit which must be the guide and teacher of the Church of the future.

I see no reason to retract or apologise for what I have said about democracy, though it will be seen that my remarks on that subject were not intended to take a prominent place in these addresses. Scores of correspondents have congratulated me on my “courage” ; but surely we have not yet so far lost our liberty in England that a man may not criticise or even ridicule a popular political theory. I called democracy a superstition and a fetish ; and I repeat that it is plainly both. The so-called “will of the people” is merely the whim of the majority. I cannot agree with Lord Morley that “the poorest and most numerous class is the People” ; it is simply the poorest and most numerous class. And a political mob has no will ; it has only passions and aspirations, which are played upon by astute demagogues, who have studied the psychology of crowds in the manner described by a masterhand more than two thousand years ago. “These mercenary individuals [the Sophists] teach nothing but the opinion of the many, that is to say, the opinions of their assemblies ; and this is their wisdom. I might compare them to a man who should study the tempers and desires of a mighty strong beast who is fed by him—he would learn how to approach and handle him, also at what times and from what causes he is dangerous or the reverse, and what is the meaning of his several cries, and by what sounds, when another utters them, he is soothed or infuriated ; and you may suppose further, that when, by continually attending upon him, he has become perfect in all this, he calls his knowledge wisdom, and makes of it a system or art, which he proceeds to teach, although he has no real notion of what he means by the principles or passions of which he is speaking, but calls this honourable, and that dishonourable, or good or evil, or just or unjust, all in accordance with the tastes and tempers of the great brute. Good he pronounces to be that in which the beast delights, and evil to be that which he dislikes, and he can give no other account of them except that the ‘just’ and ‘noble’ are names which we gave to the necessary?” 1 No imposture so gross as this could maintain itself, if it were not a real superstition. “To dispense equality to equals and unequals is to found the public order on a lie ; it is contrary to the elementary principles of human society, which rests upon the natural fact of inequality of value. . . . At the present time all political power is centred in the hands least fitted to exercise it : wisdom, wealth, culture, experience—all the most vital forces of society—are virtually ostracised.” 2 My quarrel with the democratic theory is not that it is revolutionary, but that it is utterly absurd and irrational, and that in practice it brings into power just the kind of men whom we might have expected, a priori, that it would favour. In France and the United States, politics is hardly a profession for an honourable man. The national assemblies of these democracies reflect faithfully all that is worst in the national character.

1 Plato, Republic, p. 493. 2 W. S. Lilly, Idola Fori, pp. 37-8.The charge of pessimism that has been brought against me is ridiculous. No Christian can be a pessimist. Christianity is a system of radical optimism, inasmuch as it asserts the ultimate correspondence of value and existence, or, to put the same thing in less technical language, it asserts that all will be well, some day and somehow. But optimism of this kind is a shallow mockery if it does not rest on a drastic revaluation of the goods and evils of human life, and on a firm belief in human immortality. These are both found in Christianity. The Christian doctrine, as I understand it, is that there is an eternal and spiritual state of existence, in which the Divine attributes of goodness, wisdom, and beauty are fully realised and fully operative. This state of existence we call Heaven. But since the Creator desires that those attributes which are part of His nature should be worked out, according to their capacity, by His creatures, He has caused to exist the world which we know, a world the true meaning and reality of which are to be found in moral purpose, in intellectual activity, and in art. (Religion rightly lays its stress on the first of these, without depreciating the others.) These things have all a timeless value, while almost all else fades and passes. The healthy soul loves whatever it sees to possess these values, and recognises its kinship with it. This “love” for God, and for God’s image in man and nature, is the unfailing token of spiritual health, and the hierophant of all the higher mysteries of existence. Christianity never puts its hope on temporal results, because it rates those results very low, as compared with spiritual values. Nor does it look for a millennium on this earth. The world-order, according to our belief, only exists as an arena in which the good is to actualise itself through conflict. A perfect world would have no more raison d’être. Nevertheless, as I have argued, we may reasonably expect great improvements in the constitution of human society and, which is far more important, in human nature. For the human race is an unit in God’s sight ; an unceasing purpose runs through our history. But the process of improvement will (so far as we can foresee) be so slow as to be hardly perceptible, unless indeed we discover how to breed goodness and ability as race-horses are bred for swiftness and cart-horses for strength. I confess that my hopefulness for the future of civilisation is based on the reasonable expectation that humanity is still only beginning its course. Nor can I see that it is any less agreeable to speculate on a truly rational and happy mode of existence ten thousand years hence, a hope which may be realised, than on a socialistic Utopia about 1950, which will certainly not be realised. The happiness of our remote descendants concerns us as much as that of our grandchildren and great-grandchildren. It is folly, not rational optimism, to forget that “the mills of God grind slowly,” repeating the error of those who “thought that the kingdom of God should immediately appear.”

But after all, the main argument of my addresses was not that democracy and socialism are undesirable allies because they are based on unsound principles and foster impossible expectations, but that the Church must be faithful to the example and precepts of her Founder, who declared that His kingdom was not of this world. Secularised Christianity has neither savour nor salt. True Christianity is not a religion that will ever be acceptable to the majority ; it is too stern and uncompromising. But an earnest and faithful Church, even if its adherents were in a small minority, would do a great deal indirectly towards social amelioration, by holding up a standard of public opinion which few could venture openly to neglect, and by undermining that strange amalgam of superficial culture and deep-rooted barbarism, of pride and timidity, of shrewdness and ignorance, which the New Testament calls “the World.” For the Christian standard of values, so far as it is adopted, demonetises the World’s currency, and substitutes another, which has this extraordinary quality, that it has no natural limit of increase, and that what we give to others we also make more truly our own.

The Spirits of the Age

Your committee have most kindly invited me to give four lectures on “The Co-operation of the Church with the Spirit of the Age.” It is a charming subject. It calls up quite an idyllic picture. The Spirit of the Age ! A beautiful maiden, alert, strenuous, intellectual, self-confident. Determination is written on her mouth, though some perplexity furrows her brow. She begins to doubt whether she can carry out all her great ideas unaided. When behold, there comes to meet her the Church—a still more beautiful maiden, with a serene and far-away look in her eyes ; with even more determination in her mouth, and no perplexity on her brow. Lo ! she holds out her hand to her sister, while with the other arm she points to the steep and narrow path which they must henceforth climb side by side. I have tried to conjure up this picture—that is easy ; and to bring it into some relation with actuality—that is difficult. When I quit the enchanted realm of abstractions, so full of poetry, so simple and orderly—the land where everything has a name expressing its character, and always behaves as a thing so named ought to behave—the land where things do not overlap and get entangled with each other, still less masquerade in each other’s clothes, wolves calling themselves sheep, jays peacocks, and demons angels of light—when I quit this enchanted realm and turn my eyes upon the world of reality, where things are always passing into each other without ceasing to be themselves, where nothing ever stands still to be ticketed, where instead of stable unchanging concepts we have to deal with fluctuating facts and varying values—like the mad croquet match in Alice in Wonderland, when the mallets twist into flamingoes and the hoops and balls walk about the lawn—I look about for my beautiful maiden, the Spirit of the Age, but I cannot find her. And the other still more beautiful maiden, where is she ? She, surely, cannot be hard to find.

But that is too alarming a topic, not to be tackled to-day. In my third address, if I have not frightened you all away before that time, I will approach it with fear and trembling. To-day let us examine two of our other terms—“The Age” and its “Spirit.” What do we mean by “the Age” ? When did it begin ? When we were born ? When we remembered, or forgot, to change 8 into 9 in writing the second figure Anno Domini ? There are no boundary lines in the time process, as Bergson has taught us—no beginnings and no endings. It is our intellect which always tries to chop up time into lengths. It is convenient, but deceptive. We are all very proud of our so-called historical method, which consists essentially of trying to squeeze ideas into the form of time ; but they always ooze out. However, we can cut off lengths of past time for purposes of comparison, and if we remember what we are doing, there is no reason why we should not. Let us then, obedient to our thesis, compare the twentieth century, as far as it has gone, with the nineteenth. We soon notice that our “age,” like every other age, is the rebellious child of its predecessor. The romanticists of the nineteenth century had no patience with the rationalists of the eighteenth. Wordsworth called Voltaire “dull” (we have not got Voltaire’s opinion of the Ecclesiastical Sonnets). The last quarter of the nineteenth century scoffed at Tennyson ; some of the youngest generation are tired of Browning. We are nearly all undutiful enough to want to put our parents’ household gods in the cupboard. Renan, in his detached way, said that one task which lies before the twentieth century is to fish out of the waste-paper basket the various valuable articles which the nineteenth has thrown into it. Well, it may be true that our fathers and grandfathers threw too much into the waste-paper basket ; but I will hazard the sweeping statement that the nineteenth was in many ways the most remarkable century since the beginning of history. Among its possible rivals the period which witnessed the discovery of America, the Renaissance and Reformation, Shakespeare and the printing-press, can alone compare with it for massive achievement. At the beginning of the epoch Europe shook off some of the shackles which had bound it for ages. The transition so much admired by Herbert Spencer, “from status to contract,” took full effect. There was a vast industrial development, calling into existence dense populations such as the earth had never supported before. The European races established their ascendancy over the whole planet, introducing the blessings of their civilisation to the savage peoples, whom they exterminated, and to the farthest Orientals, who are rapidly learning from us how in the distant future they may perhaps exterminate the Europeans. Such a harvest of scientific discoveries has never been crowded into three generations as the steam engine, electricity, photography, the telegraph and telephone, spectrum analysis, and the rest. In literary achievement the nineteenth century ranks only just behind the very greatest.

There are, no doubt, deductions to be made. As Houston Chamberlain says, the material element is too predominant. It was essentially a century of accumulation. Not ideas, but material gains, are its characteristic feature. Chamberlain even says : “In other respects (besides accumulation) it is neither fish nor flesh ; it wavers between empiricism and spiritualism, between liberalismus vulgaris (as it has been wittily called) and the impotent efforts of senile conservatism, between autocracy and anarchism, doctrines of infallibility and stupid materialism, worship of the Jew and anti-Semitism, the rule of the millionaire and proletarian government.” An age of ferment, no doubt ; but, in spite of its critics, one of great and almost unique achievement.

Now the great century is over, and civilisation is sitting pensively in the midst of her accumulations, like the figure of Melencolia in Durer’s famous picture. The era of scientific discoveries is happily not yet closed. The last ten or twenty years have brought to light wireless telegraphy, the transformation of chemical elements, and the aeroplane ; while great things are hoped for from bacteriology. But in all other fields signs of exhaustion are very apparent. If we were asked to pick out three great men among our own contemporaries—men whom even partial friends and admirers could without absurdity place in the same rank which the verdict of competent judges has granted to at least a dozen of the Victorians, we should find it impossible, I am afraid, to meet the challenge. There is a great deal of second and third-rate ability just now, but a dismal dearth of genius. It may be a case of reculer pour mieux sauter : the future alone can decide whether it is so, or whether we are on the down-grade ; but for the present we must face the fact that our lot is cast in a rather unpromising and uninspiring time ; the race-spirit is resting on its oars after an exhausting spurt. I do not think that this can be seriously disputed.

The results of the great discoveries remain ; but the creeds and philosophies based upon them are crumbling. In the mid-Victorian period there was a buoyant confidence that the riddles of the Sphinx had been solved, which we cannot any longer feel. Where is the cocksure complacency of the philosophic radicals, the blatant assurance of the materialistic scientists, the arrogance of Darwin’s first disciples, the calm superiority of theological liberalism ? The world now seems much more complex and mysterious ; the facile solutions which then seemed so obvious now fail to satisfy us. I am far from saying that this scepticism is a sign of degeneracy. It may be a wholesome disillusionment. Only this is plain, that while our grandfathers marched on with head erect and a confidence that victory was theirs, we are conscious of profound contradictions and unsolved problems.

I am not competent to say much about science ; but I can see that the same kind of change is coming over such studies as biology, which any student of contemporary thought can trace in philosophy and religion. It is commonly said that the mechanical theory is breaking down, and that “organic” and “vitalistic” views are taking its place. The older assumption was that we can explain the phenomena of life, even of the higher forms of life, by the principles and laws which are found to hold good for inorganic, “dead” matter. This theory was found to lead to a rather depressing materialism and determinism. Man was proclaimed to be “only the cunningest of nature’s clocks.” Religion and ethics protested against this degradation of humanity ; and it now appears that even on purely scientific grounds their protests were well grounded. Natural selection, which some of Darwin’s disciples, more confident than their master, believed to be the sufficient cause of evolution, now appears to be only negative in its action. It is a method of eliminating inefficient variations : it does not explain the fact of variation at all. And variation, or mutation, seems to be more drastic and more freakish than any one supposed twenty years ago. More and more converts are made to vitalistic theories resembling those of Lamarck, once supposed to be quite discredited. A growing mass of evidence seems to point to a kind of inner teleology, a self-directing, albeit unconscious, evolution which is much more than a mere unpacking of what was in the box all the time. “Creative Evolution” is the title of Bergson’s great work, a title chosen as a challenge to the mechanical theory which deprived the time-process of all meaning and value, by representing each stage as containing nothing that was not implicit in the stage next before it. This, we are now told, would be merely pseudo-evolution. Real evolution implies free, self-determined growth ; it implies creation, not merely unpacking and unfurling. But if this real evolution takes place, it means that the laws which govern organic life must be different from those which govern inorganic. “Why seek ye the living among the dead?” It means that the conduct of living beings cannot be predicted and calculated upon as men work out a mathematical problem ; that even if we knew all the forces, we could not, from them, calculate a necessary resultant. Free-will, once almost abandoned as a theoretical truth, though always admitted in practice, is seen to be capable of being defended philosophically. Therewith the uniformity of nature, which the mechanical scientists believed themselves to have established, though it was only a working hypothesis, is seriously threatened. Naturalistic monism is badly shaken. If inorganic nature follows one law, and life another, or if life is a law to itself, where is the unity of nature which has been such a fruitful hypothesis, the foundation indeed of all modern science?

We can trace, I think, the working of this new tendency of scientific and philosophic thought in several other departments. The grip of natural law is relaxed. Indeed, the very idea of natural law has changed. A law of nature, we are now told, is a description of the way in which nature usually behaves—nothing more. If nature chooses every now and then to behave differently, there is nothing on earth to prevent her. Creatures of habit like to have a fling now and then. So we not only see free-will asserting itself against determinism, but even miracles are rehabilitated. The supernaturalist once more confidently urges his own method of bringing together matter and spirit by dovetailing them into each other in the world of phenomena ; and the pragmatist, with exultant war-whoops, dances on the prostrate form of absolute idealism, and claims that whatever satisfies human needs is true—truer at any rate than anything which does not, since truth is only a pedantic synonym of usefulness.

But the victories of natural science, won, all of them, under the banner of the uniformity of nature, are too recent, and the confidence in scientific method is too great and too well-grounded, for scepticism to make much headway within the proper frontiers of nature-study. Science pursues her well-tried methods, and the results continue to be satisfactory. And supernaturalism—the theory of occasional interventions—belongs to the psychology of religious belief rather than to strict science or philosophy. It is a bridge to connect the worlds of nature and spirit ; it is not a theory which science and philosophy need take much account of as affecting their own researches. The most remarkable product of the undecided conflict between mechanism and vitalism is the sceptical or sophistical theory of knowledge which in philosophy is called pragmatism, and which in theology is the basis of modernism. Religious activity in this century will be marked, I believe, by the conflict of two schools, the one rationalistic, strongly ethical, and Protestant ; the other, half sceptical, half superstitious, frankly adapting itself to “human needs,” lower as well as higher, and maintaining a dualistic severance between truths of faith and truths of fact. This is modernist Catholicism : it is indeed the way in which Catholicism has fought its campaigns for the most part ; but it was extremely naive of the modernist priests to think that they could give away the arcana imperii with impunity.

We have found, then, as the first of our “tendencies of the present age,” this revolt against mechanical and determinist views of human life. Our generation, as compared with its predecessor, is disposed to believe in free-will and spontaneity. It can give a good account of itself in rejecting the older mechanical theory. But since the real laws, if there are any, which control the higher forms of life are not yet discovered, there is a great deal of wild and chaotic theorising about the relations of mind and matter, and a recrudescence of puerile superstition which almost makes one wish back again the iron hand of Victorian naturalism. We must hope, however, that the extravagancies of this newly found liberty will be pruned away.

These intellectual movements are only recognised by a few, though a thoughtful observer can trace their ramifications almost everywhere. But for the man in the street, the tottering of the great industrial fabric of the nineteenth century dominates all other issues.

Under the old regime of status, competition was never very keen ; and at first the new individualistic industrialism seemed only to stimulate a healthy rivalry which got out of each man the best work that was in him. But every system carries within itself the seeds of dissolution. We need not recount again the too familiar tale of how men, rather than their tasks, have been subdivided, how work has been dehumanised and despiritualised ; how the speeding up of these monotonous processes imposes an intolerable strain on the nerves of the worker ; how the conditions of town life have ruined the physique of the labouring class ; and lastly, how various causes combine to make us breed from our worst stocks, so that a progressive degeneration is taking place.

To any one who is able to view the situation without prejudice or passion, the outlook is disquieting in the extreme. We amassed a population of 46 millions on two small islands, while Englishmen were making England the workshop of the world. Great Britain has enjoyed certain accidental advantages of which we have made full use. Our position just off the mainland of Europe gave us the advantage in securing the Atlantic trade ; we have coal and iron in abundance, and close together ; we have had in the past good and cheap labour. Of these advantages some are passing away inevitably, others are being wantonly sacrificed. America is now the natural centre of the world’s commerce, because the Pacific is becoming as important a trade route as the Atlantic ; we are no longer the most favoured nation geographically. Our coal supply is being exhausted with criminal recklessness. And our labour is no longer very good, and is becoming extremely dear. We cannot long remain the workshop of the world under these changed conditions. As surely as water finds its own level, so surely will the transfer of industries and wealth, first to America and then to Eastern Asia, be the necessary sequel to the European labour movement.

In this country, at any rate, the twentieth century is the spendthrift heir of the nineteenth. The working-man seems to have resolved to make himself comfortable by taxing capital—in plain terms, by looting the accumulations of Queen Victoria’s reign, and living on the rates and taxes. He will have, I think, a short life and a merry one, and his children’s teeth will be set on edge.

For these reasons I cannot join the chorus of the lay and clerical advocates who, when they tell us to “co-operate with the spirit of the age,” really mean that we should co-operate with the labour movement. Socialism, or almost any other experiment, might answer in Australia, till the British fleet ceases to patrol the ring-fence ; but in England I fear that the conditions are ideally unfavourable for those who hope to see a dense population with high wages and short hours.

Let us listen to some other popular cries, and see whether they seem more hopeful as a basis of “co-operation.”

It is, or ought to be, a commonplace that the very first duty of any one who wants to understand the signs of the times is a critical examination of current shibboleths and catchwords. Mankind is just as prone as ever to create fetishes. The only difference between us and the savage is that he makes an idol of wood or stone, while we dress up some misunderstood idea in fantastic clothes, and worship that. We light a fire and compass ourselves about with sparks, as the Old Testament prophet said, and then we dance round it, invoking the name of our god. It is quite as easy to hypnotise oneself into imbecility by repeating in solemn tones “Progress, Democracy, Corporate Unity,” as by the blessed word Mesopotamia, or, like the Indians, by repeating the mystic word “Om” five hundred times in succession.

The catchword Progress I shall leave for my next address. A great deal of nonsense about Progress has been and still is talked ; but we are losing faith in it—indeed, I think rather too much. Some of our newest guides deny that any progress—any real progress as distinguished from mere accumulation of experience—can be traced in humanity itself. That seems to me too pessimistic, and not to be borne out by a candid study of history.

Democracy is perhaps the silliest of all fetishes that are seriously worshipped among us. The method of counting heads instead of breaking them is no doubt convenient as a rough and ready test of strength ; and government must rest mainly on force. It is also at least arguable that democracy is at present a good instrument for procuring social justice, and for educating citizens in civic duty. But that is really all that any one has a right to say in its favour. To talk to the average Member of Parliament, one might suppose that the ballot-box was a sort of Urim and Thummim for ascertaining the divine will : that the odd man enjoys a plenary inspiration, like the Bishop of Rome when he speaks ex cathedra. This superstition is merely our old friend the divine right of kings (“the right divine of kings to govern wrong”) standing on its head ; and it is even more ridiculous in that posture than in its original attitude. There is absolutely no guarantee in the nature of things that the decision of the majority will be either wise or just ; and what is neither wise nor just ought not to be done. This is a somewhat elementary truism to enunciate to an intelligent audience ; but there stands the ridiculous fetish, grinning in our faces, and the whole nation burns incense before it. It is, I think, our duty to challenge any one who talks of the “right” of the majority to do whatever they think fit, as follows : “Your statement implies one of two things. Either you believe that the majority of every political aggregate is divinely inspired with wisdom and justice, which is a gross and absurd superstition ; or you assert, with Thrasymachus in Plato’s Republic, that justice is only a name for the interest of the stronger ; a doctrine which the conscience of humanity agrees with Socrates in stigmatising as grossly immoral.” After that, you will not need to ask my opinion of the bishop who published a sermon called “The Democratic Christ and His Democratic Creed.” It was not thus that our Master brought comfort and strength to the weary and heavy laden.

“ … One of the preachers in a collection of sermons on social subjects published in England was not ashamed to call his sermon “The Democratic Christ and His Democratic Creed … ”

-W.R. Inge, The Social Message of the Modern Church (1926)

Corporate unity is another catchword which needs critical examination, but in a more respectful tone. I shall have more to say about this in my third address, when I deal with “The Church.” Here I will only say, first, that a corporate whole is constituted by its internal harmony and consistency, not by the rigidity of the spikes which it interposes between itself and those outside. Next, that the comparison of a society to an “organism” is only an analogy, and one that does not correspond very closely with the facts. A human person has far more independence over against society than a hand or foot over against the whole body. Society exists for him as well as he for society ; indeed it is an unjustifiable and very misleading personification of an abstraction to speak of the State as having rights and duties apart from the individuals who compose it. Above all, we belong to a great many social organisms, each with indefeasible but limited claims upon us. We cannot admit that all other organisms (“organisations” would be a much better word) are, as we are sometimes told, only “organs of the State.” The family, for instance, and the Church, are much more than this. The main problem of practical ethics is to adjust the rival claims of the various organisations to which we belong ; and, in dealing with this problem, declamations about corporate unity do not help us at all. We have our duties to our family, to our neighbours, to our profession, to our country, to our Church, to the comity of civilised nations, to humanity, perhaps to the whole cosmic process so far as we understand it. We must strenuously resist any claims on the part of any one of those aggregates to enslave or deny the rights of the others. “Honour all men ; love the brotherhood ; fear God ; honour the King.”

There are certain other currents of opinion which, though they seem to me more local, more superficial, less likely to continue, than those with which we have been dealing, must not be left out unconsidered. There is the counter-revolution provoked by the orgies of 1793, which, in opposition to liberalism of all kinds, created a revival of mediaevalism in architecture, art, and religion. History seems to show that revivals are always only stop-gaps. They indicate that existing institutions are not giving satisfaction or doing their work properly ; they generally do some good service by “pulling out of the wastepaper basket” some objects of value which have been too hastily thrown into it ; they create a sentiment of sympathy with the past ; they emphasise the essential identity of human needs at different periods ; but as revivals they have their day, and pass. The past can never be reconstructed ; history never repeats itself—it only resembles itself.

In ethics we have a well-marked humanitarian movement, and a violent revolt against it, in the philosophy of Nietzsche. On one side, this humanitarian movement marks a real progress, which we may hope will be permanent. The brutal and stupid cruelties which were allowed to disfigure our civilisation till the last century now fill us with amazement. But there is a soft and flabby side to modern humanitarianism which is the result of a long peace and industrial activity. The horror of taking life under any circumstances seems to me unnatural, and probably only temporary. The State of the future, I believe, will kill mercifully but freely.

Another temporary current which is already losing its force is that of nationality, patriotism, or imperialism. It draws its power from a blend of noble and ignoble sentiments. We call it noble patriotism in ourselves, and brutal aggressiveness when it is displayed by the Germans. It is a sentiment which is perhaps falling out of touch with facts, since the European nations have a common civilisation, and the classes in each nation have much more in common with the same class in other countries than with other classes in their own. So it is plain that international combinations, in the interests of capital, labour, the Church, learning, research, &c., are taking, and in the future will more and more take, the place of geographical divisions. If men were reasonable beings this ought to bring to an end the monstrous waste of our resources upon armaments.

Well, “the spirits of the age” do not come very gloriously out of our scrutiny. My next address will be more cheerful in tone, for I do believe in the progress of humanity, though I believe it is painfully slow, and that it advances in spirals, “with many a backward-streaming curve.” We happen to be living at the end of a very great and remarkable period, and we must not be discouraged if no very great achievements are reserved for our generation. “Show thy servants thy work, and their children thy glory,” may be the most appropriate prayer for us. And if certain aspects of the immediate future appear somewhat dark, we must remember in the first place that perhaps the worst moments of life are those in which we are weeping over misfortunes which never come, and secondly that to God, who has all eternity to work in, it matters little if His purposes are thwarted for a season ; nor need it trouble us very much if we believe in our own immortality.

How many new ‘spirits’ have appeared since the time of this writing? -Editor.What can We Do?

I have been dealing rather roughly and disrespectfully with some idols of the market-place, before whom I suspect that some of you are in the habit of throwing flowers or grains of incense. You have not, I hope, inferred that I am flippant or cynical about the possibility of doing good in our generation, and doing it as church-people. It is not so ; but the marketplace is just now unusually full of idols, some of which badly want breaking. Besides, what is the use of retailing once more those unctuous commonplaces about the downfall of individualism, the duty of trusting the people, the Church’s care for the suffering and toiling masses, and the recovery of the idea of corporate unity? Shibboleths and catchwords are useful as labels—(those who utter them we call our friends, those who don’t are enemies or suspects)—as missiles, as war-cries (to excite us to a Christian pitch of pugnacity) ; and sometimes they are very soothing, when like-minded persons get together and administer them to each other ; but they have the most fatal effect on sane thinking. If the devil invented partisan labels—and I think he must have done so—it was one of the cleverest tricks he ever played. In practice, I think these shibboleths or platitudes cover much confusion of mind and irrationality of conduct. So I have treated the so-called spirits of the age with considerable freedom. I have declined to burn incense to democracy, or socialism, or “corporate unity,” or any of them. The Spirit of the Age, I have maintained, is no true spirit unless she is also the Spirit of the Ages. Her aims are not bounded by this generation, or this century. Her thoughts are much deeper, her outlook much wider. We must probe deep to discover what she thinks and intends.

And “the Church” must not be identified quite unhesitatingly with any particular institution or denomination, nor with tendencies which seem to be dominant in our generation. The Church is an idea in the mind of God, a vast design which is to be worked out in time, requiring probably tens of thousands of years to reach its full development—its “nature,” as Aristotle would say. We are not in a position to dogmatise about the Church, because by far the longer portion of its history—that portion, too, which will explain and give its character to the whole—is still in the unknown future. The true Church of the present consists, if we could see it, in those elements in our religious societies, which are capable of being worked up into the Church of the future : the gold, silver, costly marbles, which will survive the testing fire, and will be thought worthy of a place in the temple of God, which is being slowly built upon the one foundation which has been laid once for all. We can judge pretty well what are good materials ; it is the designs of our little architects which give us pause. They constantly have to be pulled down, with great trouble and loss of time. And when we see these architects ambitiously building against each other, we rather grudge them the admirable material which they are often able to get, though it is usually mixed with very inflammable stuff—wood, hay, and stubble. Shall we put it thus,—That all which is truly Christian in our age is part of the Church, and belongs to the Church ; but it is not yet built up into its final position as a portion of the “glorious Church” (

Remembering, then, that we are much better judges of good and bad material than of the way in which the wise Master-Builder will ultimately decide to use the good material, what can we do to help things forward in our generation? Can the Church of England, in its “corporate” (blessed word !) capacity, do anything to help this country to work out its salvation and finish the work that God gave it to do ? Let me first indicate three pitfalls which we shall do well to avoid, and then (at last ! you will say) come to a constructive policy.

There are three blunders which a Church is prone to make when it aspires to influence the world as an institution. These three are wonderfully symbolised by the three temptations of our Lord. The narrative of the Temptation, when read in this light, as a warning to the Church of the three insidious traps which the devil intended to set for her, is one of the most remarkable passages in the New Testament. First of all is the temptation to try to reach men’s souls through their stomachs, to make a bid for popular favour by offering material advantages. There are very many irreligious people who would be quite ready to say with Jacob, “If the Lord will give me food to eat and raiment to put on, then shall the Lord be my God.” This is the false road to success, symbolised by the first temptation. There never was a time when the temptation was so great as it is to-day. The Church as an institution has always been disposed to truckle to the powers that be. I need give no instances of this humiliating and indisputable truth. Formerly it was “the right divine of kings to govern wrong,” that resounded from every pulpit. Now that the masses are becoming conscious of the power which democracy puts into their hands, now that they are waking up to the fact that they have their former masters on the hip, the devil whispers insidiously that the Church may make the most of the obviously anti-plutocratic leanings of the Founder, and do a good stroke of business for itself at the same time. Our clergy are positively tumbling over each other in their eagerness to be appointed court-chaplains to King Demos. I am afraid this is what is in many people’s minds when they talk of co-operating with the Spirit of the Age. Let the Church strike a bargain with the Labour Party. Let the clergy abuse capitalists and abet strikes from the pulpit. Let them advocate schemes for the forcible redistribution of other people’s property. In this way only there is hope of “winning the masses.”

Now I am not so unfair as to suppose that no generous and truly Christian motives are mingled with this desire to see the Church plunge into the arena of social strife. The Christian socialist says truly, that so long as the majority of the clergy belong to the upper and middle classes, they will tend to be imbued with the convictions and prejudices of those classes ; and that it is very undesirable that the working-man’s point of view should not be recognised by those who labour among them. The sufferings of the poor are often very real, and it is right that Christians should wish to see them relieved. The present distribution of wealth is absurd, and, if we believe the Gospels, it must be a greater misfortune for those who have too much than for those who have too little. All that is very true ; and I cannot dispute the justice of the remark which Jowett once made, in his detached way : “I am afraid there is more in the Gospels about the danger of being rich and the advantage of being poor, than most of us are willing to admit” ; nor even the Bishop of Oxford’s words that he had a permanently troubled conscience on the subject, because, while the social position and incomes of the higher clergy place them, and are meant to place them, in the upper, or upper middle class, the Gospel, so far as it takes sides at all, is on the side of the poor and not on the side of the rich.

Nevertheless, I can conceive of nothing more fatal than the policy of enlisting the organised forces of the Church on the side of militant labour. I can recall no instance of a Church which has gone into politics and has not come out badly smirched. Moreover, there are radical and fundamental differences between the view of life taken by social democracy and the view of Christianity. Put shortly, socialism always assumes that the stye makes the pig, while Christianity declares that the pig makes the stye. Socialism really agrees with the Northern Farmer, that “the poor in a loomp is bad,” and that the way to make them good is to see that they “have coats to their backs and take their reg’lar meals.” The consistent socialist hates eugenics as much as he hates Christianity, because that science maintains that nature is more important than nurture. Christianity not only maintains but proves triumphantly that the highest life may be led in extreme poverty ; though I will state my opinion that we may infer from the teaching of our Lord that He regarded a simple sufficiency—the lot of the well-paid artisan or the small professional man or farmer or tradesman—as the most favourable condition for the higher life. The twelve apostles seem to have belonged to this class. But we can hardly assert too strongly that our Lord set a very low value on the apparatus of life. No religion not based on harsh asceticism and contempt for civilisation (and Christianity is quite free from this error) ever valued the accessories of life so lightly as the Gospel does. If we take all the Synoptic Gospels together (I admit that St. Luke alone might give a different impression), we shall be struck by the aloofness which our Lord maintained towards economic questions. The refusal to divide the heritage (“Man, who made me a judge or divider over you?”) is not to be explained away, especially as we find the story in St. Luke, who, like St. James in the Epistle which bears his name, shows unmistakable traces of the hatred of the rich which was a Jewish tradition. The poor man in the East is always a wronged man, because he cannot afford to buy justice, which is always for sale in those countries. And the Jew is the last man to sit down tamely under such treatment. Sufferance may be the badge of all his tribe ; but he never ceases to dream of the pound of flesh, and generally gets it sooner or later. But our Lord’s attitude was quite different. He says to the grasping moneygrubber not “Thou thief,” but “Thou fool.” The covetous man is one who is so misguided as “propter vitam vivendi perdere causas.” He has assumed that life is only a livelihood. Therefore our Lord reiterates such warnings as, “A man’s life consisteth not in the superabundance of the things which he possesseth,” “Is not the life more than meat, and the body than raiment ? ” These are the most characteristic utterances of our Lord about money. Mammon is an exacting master, who will accept no half-hearted service. The American or the English business man knows the truth of that only too well. And God is also an exacting Master, who will accept no half-hearted service. As Huxley once said, with more insight and sympathy than he usually admitted for the religion which he rejected, “It doesn’t take much of a man to be a Christian, but it takes all there is of him.” Therefore, we must choose whom we will serve. If we choose wrong, we may incidentally inflict superficial injuries upon our neighbours ; but it is we ourselves who will suffer most. “So long as thou doest well unto thyself, men will speak good of thee” ; and these are the men who, if we believe our Master, are their own worst enemies. Well, the tone of this teaching is quite different from the declamatory praises of voluntary poverty, and rhetorical invectives against avarice, which are sometimes quoted from Ambrose and other Christian Fathers by our Church-socialist friends. This kind of preaching comes not from Christ, but from the Roman rhetorical schools. You will find it at its best or worst in Seneca, “the father of all such as wear shovel hats,” as Carlyle unkindly called him ; and Seneca, as Nero’s prime minister, accumulated a fortune of three millions sterling in a few years, in the intervals of composing these most edifying harangues.

The revolutionary party has long ago made up its mind about Christianity. “The idea of God must be destroyed,” said Marx, the founder of the collectivist theory : “it is the keystone of a perverted civilisation.” “The first word of religion is a lie,” said his chief lieutenant, Engels. “The revolution denies religion altogether,” says Bebel, the leader of the social democratic party in Germany. “Socialism utterly despises the other world,” says Mr. Belfort Bax. These men see very clearly that Christianity takes all the sting and fury out of revolutionary agitation. (Of course, it also takes the sting and fury out of the resistance to economic changes ; but this they do not think of.) I have good hope that the working-man will not be permanently irreligious and materialistic. At present I think he is no better and no worse than other classes in this respect. We may be sure that many of the handworkers—though not the majority, I fear, of this or any other class—will turn to that Leader who alone can help us, and will take the light yoke and easy burden upon them. But there must be no unholy alliance with a movement which at present is to a large extent based on fundamentally wrong principles. It is treason against our Lord, against His Church, and against the labouring classes themselves, if we secularise our message, and fill our sermons, as some are doing, with echoes of the class-warfare. It is treason to tell them that Christianity has repented of its “otherworldliness,” and is now more worthily occupied with parish councils and strikes and free meals and poor-law reform. It is our duty to maintain, in the face of those who nickname the clergy “sky-pilots,” that it is otherworldliness which alone has transformed, and can transform, this world.

Otherworldliness, remember, is not belief in a future state of material happiness and misery, in which the inequalities of the present life are to be redressed with interest It is no invention of the privileged classes, intended to make their less fortunate neighbours content with their lot. That is the mistake of men who can realise no happiness that does not depend on external conditions, and who therefore misunderstand fundamentally the nature of the Christian promise and the foundations of Christian joy. Otherworldliness simply means the conviction of the immeasurable superiority of spiritual goods over material. It maintains that the “transvaluation of all values,” which Christ came to establish, is no imaginary thing, but the revelation of actual fact. There are some gains which can only be appropriated at the cost of another’s loss. There are some good things which can only be transferred to Peter by robbing Paul. With these Christianity has nothing to do. But there are other good things, of a much higher, more durable, and more satisfying kind, in which one man’s gain is not another man’s loss ; which are unlimited in amount, and indestructible. They belong to the unseen, eternal world, which Christianity maintains to be the real world—the world of which we are citizens. If we once allow this eternal background to drop out of our teaching, we are building on a wrong foundation, and are no longer heralds of the good news which we were ordained to proclaim.

As Christians, we have nothing to do with mankind “in a loomp,” whether poor or rich. Let us hear no more of “winning the masses.” That is a phrase for politicians, not evangelists. There is not the slightest probability that the largest crowd will ever be gathered in front of the narrow gate. I sometimes think that our absurd superstition about the sanctity of the ballot-box, as an infallible machine for extracting wisdom and truth, has affected our faith. We are actually uncomfortable at being in a minority. Far more wholesome was the state of mind of the statesman who, when his speech was applauded by the mob, said uneasily, “Have I said anything very foolish?” Christianity always appeals directly to individuals ; and its influence radiates out naturally from its focus in the individual soul. That influence is always strongest in the smallest, weakest in the largest circles. If we ally ourselves with mankind “in the loomp,” we shall ally ourselves with mankind at its worst. It is an unpleasant truth ; but one which needs emphasising at present. Bishop Creighton says very truly : “Christianity beautifies many an individual life, and sheds a lustre over many a family. Its influence is less conspicuous in the life of business ; it pales in the sphere of what is called society, and is still dimmer in politics ; in the region of international obligations it can scarcely be said to exist.”1

1 The Heritage of the Spirit, p. 181.The second temptation of Christ, which, if I am right, symbolises a permanent temptation of His Church, is to trust to miracles, or, as we might perhaps put it, to short cuts, or, remembering the story of the Gordian knot, to cutting knots which should be untied. The laws of the moral and spiritual life are just as inexorable as those of the physical world. Nothing worth having is given away ; all must be earned. There is no way of dying the death of the righteous except by living the life of the righteous ; no way of seeing God except by being pure in heart ; no way of believing rightly except by thinking honestly. The lower religions, which are by no means dead (“there are some dead men who have to be killed again in each generation,” as a Frenchman said), are mainly fallacious attempts to evade this great law. The whole system of religious magic, with its accompanying demand for “the sacrifice of the intellect,” is simply this old temptation. “Cast thyself down, for he shall give his angels charge over thee,” they tell those who come to them. Laws will be suspended in your favour ; we can let you in by private ticket, without much personal trouble. This error is not confined to one school of thought in the Church. It matters little whether cheap forgiveness is oflFered as the result of the magical efficacy of the Sacraments, or as the result of being “washed in the precious blood of the Lamb.” In either case it is false. Spiritual laws are inexorable. Whatsoever a man soweth, that shall he reap—that and nothing else. We are always sowing our future ; we are always reaping our past. There is no short cut to the City of God, for men or nations.

The third temptation is, of course, to use questionable means, such as violence and fraud, in the service of the Kingdom of God. It affects our present problem, “The Co-operation of the Church with the Spirit of the Age,” in this way. Our Lord always appealed to men by what was best in them. Zacchaeus craved for human sympathy, and as soon as he found some one who was willing to treat him as a man, and not as a dog, was willing to go through fire and water for him. The poor woman who washed his feet had a loving heart, and could win pardon through her love. It was always the same. Jowett (to quote this half saint, half cynic again) said that “You cannot do anything in managing men without being a bit of a rogue.” Jowett’s roguery, though it existed, was not of a very shocking kind ; but Christ entirely refused to use any policy of this sort. This alone makes it almost impossible for a Christian to mix much in politics, except as one of those impracticable people who can’t be bought or bargained with, and who therefore have to be either excluded as hopelessly unpractical, or reckoned with as irreconcilables. When we remember the colossal amount of evil that has been wrought by unscrupulous diplomacy in a good cause, especially by the readiness to take advantage of and utilise the moral defects and weaknesses of others, the vanity of one, the jealousy of another, the avarice of a third—that “knowledge of men” which goes for so much in the art of management—we shall feel the profound significance of this third temptation. There is hardly a single great moral movement which has not been wrecked by getting into the hands of clever, ambitious, unscrupulous schemers. The Church must never “get hold of people,” except by their best side. There is a good passage in Mrs. Bosanquet’s book, The Strength of a People, which I should like to quote in illustration of what I have been saying. “In all considerations of social work and social problems there is one main thing which it is important to remember—that the mind is the man. If we are clear about this great fact, we have an unfailing test to apply to any scheme of social reformation. Does it appeal to men’s minds ? Not merely to their momentary needs, or appetites, or fancies, but to the higher powers of affection, thought, and reasonable action. The necessity for this appeal has, of course, never been entirely lost sight of. Leaders like Cromwell, who insisted that you could not even make a good soldier out of a man without appealing to his higher qualities, owe their success to their profound knowledge of human nature. Great religious teachers, who have put their faith in spiritual conviction and conversion, who have refused to accept anything short of the whole man, have achieved results which seem miraculous to those who are willing to compromise for a share in the souls they undertake to guide.”

Avoiding these snares, what is the Church to do, or rather, what are we humble individual Church people to do, in order to make our faith in Christ an effective force in the social life of our country ? Let me put the question in this form, and leave the Spirit of the Age to take care of itself. The deepest Spirit of the Age is on our side ; the superficial currents we don’t care about, and are certainly not going to float with. How can we best, as Christians, serve our fellow-men ?

I am strongly convinced that our whole duty is this—to hold up the Christian view of life, the Christian standard of values, steadily before the eyes of our generation. To live by that standard ourselves ; to show that we are not ashamed of it, that we find that it works, that we are ready to defend and justify it to all questioners. It is hardly necessary in this company to enlarge upon the characteristic features of the Christian view of life. We all know the unique stress which our Lord lays on love and sympathy ; how He taught us to regard God as a Father to whom we have immediate access at all times and in all places ; how He broke down all the barriers, sacred and profane, that separate man from man ; how He made everything depend on inwardness — the moral motive of action ; how He taught the duty of hopefulness and trust, condemning worry and anxiety ; how He taught the necessity of absolute sincerity and single-mindedness ; how He advocated plain living without harsh asceticism ; how He transformed all values in the light of our divine sonship and heavenly citizenship ; how He drew the sting of death by making it the gate of life, and (as part of the same law) showed us how we must die daily to sin, and be reborn unto righteousness. We are to use these convictions of ours in helping to form public opinion, and in setting a standard to others. We may do great good by paying honour where honour is due, and by treating successful rascality with open refusal of respect. We can set an example of simplicity in our way of living, thereby making social amenities easier for the poorer members of our own class, and indirectly for the class below, who are injured, not benefited (as is still often absurdly supposed) by the lavish expenditure of the rich. Nothing is at present more desirable than that the reckless wastefulness of our habits—the fault pervades the whole of society from the millionaire to the day-labourer—should be checked. We can set our face against immoral, extravagant, or foolish fashions, reviving some of the wholesome austerity of the old Puritans, Quakers, and Evangelicals ; we can try to save what may be saved of the old English Sunday ; we can protest vigorously against betting and gambling, including all card-playing for money ; and there are many other ways in which we might show that the Church conscience is a real social force, no weaker than the famous “Nonconformist conscience,” which is sometimes no more than a rather tortuous and greasy instrument of party politics.1

1 Some Nonconformist ministers affected to be very indignant at this sentence, which they construed as a personal insult. I am no enemy to the English and Welsh dissenters ; but I think that their habit of mixing religion with politics has almost ruined their spiritual influence in the present generation. There are more ways than one in which “connection with the State” may pervert the energies of a religious body. My words had obviously no reference to Scotland.These rules of conduct can hardly be called co-operation with the Spirit of the Age. They are rather protests against it. But I think we may find a few modern tendencies which we may, as Church-people, welcome and desire to assist.

The breaking down of class barriers is surely a good thing. Although it is the height of absurdity that every adult male, however foolish or vicious, should have an equal share in governing his neighbours and deciding the policy of the country, it is certainly right that no man should forfeit his citizenship by following a poorly paid calling. And democracy is teaching us, I hope, that there is no reason whatever why a gardener or a bricklayer should not be as good a gentleman as a squire or banker or clergyman. Let us once for all get rid of the snobbish idea that the dignity of our work depends on the kind of work it is, or, worse still, on the scale of our remuneration, instead of on the spirit in which it is performed. Clergymen and teachers are especially in need of remembering this obvious truth. So far is it from being true that the aristocratic ideal (to which I attach great importance) is dependent on class distinctions, that I will boldly maintain that class distinctions ruin that ideal in practice. Those who have studied the social life and habits of the upper classes in the eighteenth century will understand what I mean. Political equality is the caricature of a great truth—that all human beings are essentially equal, in this sense, that the moral personality is inviolable. No man or woman is to be merely used, used up, or dishonoured. So far, democracy is reminding us of one of the most original and important parts of the Christian message, and we may “co-operate” without hesitation.

Akin to this is the spread of education. We can never forget that striking passage in which Carlyle compares the untaught masses to a people that had had their right arms maimed. The object of education is to enable every one to make the best of himself. Not necessarily to “better himself” ; that ideal could only result in intolerable stress of competition, or an “educated proletariat.” When it is once admitted that there are only two claims to respect which can be recognised—character and intellect—(a Platonist would add beauty, perhaps rightly), and that it does not matter a pin what a man’s trade is, so long as it is an honest and useful one, a more healthy tone about education will follow. As a Church, we may throw our influence into the scale in favour of sound ideas about education. And if we are as keen about the interests of sound secular education as we ought to be, we shall try to settle the wretched squabble about denominational religious teaching in primary schools in a statesmanlike way, thinking not so much of scoring points for our own denomination as of helping those who want to make our national education efficient and rational.

Thirdly, the care of public health, and the new science of Eugenics, ought surely to have the enthusiastic support of the Church. Progress is only possible if Nature and Nurture are both improved. The betterment of external conditions is the method which produces the quickest results ; but these improvements are superficial, precarious, and in part illusory. The real test of progress is the kind of people that a country turns out. No political machinery will work well if the population is of a poor type, physically, mentally, and morally. The ehmination of inferior stocks, and the encouragement of the superior to multiply, are absolutely necessary if social degeneration is to be prevented. We have inhibited natural selection ; rational selection must take its place.

This gives another reason why the Church should set its face against luxury. Luxury destroys every class or nation that practises it. Nothing fails like success ; it kills off families more surely than any oppression that falls short of slavery. A great deal of rabid nonsense has been talked about race-suicide—the births in this country still exceed the deaths by nearly two to one—but the luxurious classes are actually failing to keep up their numbers ; and this tendency means that many of the strongest and ablest families are dying out. Edward Carpenter was not far wrong in treating “civilisation” as a racial disease ; few races have survived it very long. But now that we know the nature of the malady, and the remedy, we ought to be able to avoid the blunder of sacrificing the higher gains for the lower. Science will soon give us a definite programme of race-hygiene.

These paragraphs show that even Dean Inge was not immune from being seduced by some of the spirits of his age. If even he could not escape the snares entirely, how much more ought we exercise extreme care? -Editor.These three, I think, are all on right lines. But the main work of the Church must always be to influence the characters of individuals. Listen how St. Augustine apostrophises the Catholic Church :—

“Not only dost thou teach men to worship God with the greatest purity, but thou also teachest them to love their neighbours with a charity which can cure all the evils which sin brings upon human nature. It is thou who bindest wives to their husbands by a chaste and faithful obedience, and husbands to their wives by the laws of sincere love, who makest children subject to their parents by a kind of free servitude, who givest parents a religious authority over their children, who drawest tighter all the bands of nature and of family. Thou makest servants submissive to their masters, masters gentle to their servants. Thou bindest citizens to citizens, nations to nations, in a word, all men to each other, making them not only one society, but one family, by reminding them of their common origin. Thou teachest sovereigns to desire the good of their subjects, subjects to obey their sovereigns ; thou prescribest to each of us, to whom we owe honour, affection, awe, consolation, advice, exhortation, reproof, punishment ; finally, how we ought to be just and charitable towards all.”

Does this sound very old-fashioned ? Nevertheless, I think St. Augustine was right, and that, as a rule, the duty of the Church is to accept secular institutions and make them work well. We need not be afraid that this will land us in that kind of unprogressive Toryism which stands with both feet firmly stuck in the mud, and says, pompously, “J’ y suis ; j’ y reste.” There is no such lever for moving society as religious faith. It really moves society, just because it alters the will and character of individuals. There is no political alchemy whereby you can get golden results out of leaden instincts. But make the tree good, and its fruit will also be good. I think we have the highest authority for believing that this is the best, nay, the only true method of social amelioration.